By now you’ve heard it. The smash of 2017, “Despacito” has topped the charts in nearly 50 countries, including an unprecedented run on the U.S. Top 40 for a Spanish-language song. It is now the most viewed and liked video on YouTube of all time, the fastest to rack up 2 billion views and the first to reach 3 billion — and in barely six months, a benchmark that took two years for Wiz Khalifa and Charlie Puth’s “See You Again.” By YouTube’s count, the people of the world have collectively watched “Despacito” for 20,000 hours. No doubt, we’ve sung and danced along for far longer than that.

Unlike the “Macarena,” the song is not a silly novelty. It’s a hit on its own terms, a sexy Spanish sing-along with no special hook aside from its catchy refrains and insistent beat, and it was well on its way before Justin Bieber pulled a Pitbull and jumped on the bandwagon (and gave it a push). A phenomenon like “Despacito” invites speculation and demands analysis. As someone who has studied the history of reggaeton and Caribbean music in the United States, especially in the age of the internet, I have been as fascinated by “Despacito” as anyone. Why this song? Why now?

While I don’t believe in any single magic explanation for the remarkable resonance of “Despacito,” there are a few crucial factors that are worth our attention if we’re curious about this momentous occasion in American and global popular music.

The first is relatively straightforward but not to be neglected: simply put, it’s a good pop song, combining decades of songwriting experience, a weaponized chord progression, inspired performances by seasoned professionals, and access to an international music industry. The second factor helps to explain why “Despacito” was able to break out of the Latin pop realm and into the Anglophone and the global: Audiences had been primed to receive a pop-reggaeton song in the midst of an ongoing and unabated vogue for “tropical” sounds. While either of these two factors could have applied to previous historical moments in pop, the third is the one that most clearly locates “Despacito” in the early 21st century: in short, YouTube.

Taken together, these factors reveal “Despacito” to be a complex, profoundly collective phenomenon that points as much to the past — whether Tin Pan Alley, San Juan, or Kingston — as it does to the future, to a world remaking global pop in its own image.

Classic, Savvy Songwriting

For listeners encountering Luis Fonsi for the first time, he may seem an unlikely crossover star, but he’s been charting this path his entire life. Born in Puerto Rico, Fonsi showed an early interest in music, inspired by Menudo, the Puerto Rican boy band that gave Ricky Martin his start. At 11, he moved to Orlando where he later attended the same high school as DJ Khaled, who was a few years his senior, and NSYNC’s Joey Fatone, whom Fonsi met in chorus class. Fonsi and Fatone began their performing careers doing a capella versions of Boyz II Men songs together. In 2002, Fonsi opened for Britney Spears in Orlando on her Dream Within a Dream Tour, and in 2009 he sang at Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize concert in Oslo. In the meantime, he established himself as a force in Latin pop, a romantic balladeer belting boleros, bachatas, and pure power-pop en Español. No outsider to the mainstream, Fonsi could hardly have envisioned hitting quite like this. But he prepared to.

Fonsi’s co-writer on “Despacito,” Erika Ender, was the first ringer he enlisted. Born in Panama, Ender also spent formative years in Miami and brings a cosmopolitan fluency and versatility to her craft. Over the last 25 years, she has contributed to over 40 hit singles in multiple markets, and among other accolades, won a Latin Grammy for a regional Mexican song she wrote for Los Tigres del Norte. Together with Fonsi and his guitar, they penned a song that is sensual but not easily objectionable — and deeply catchy, a semi-salacious song stacked with hooks, taking a page from recent pop songs with their pre-choruses and multiple refrains. That said, “Despacito” takes its time getting to the first chorus, even adding an extra beat and a half before it drops, as if to riff on the central premise of the lyrics: Let’s go slowly, so we can last all night. But despite no lack of innuendo, “Despacito” avoids the direct portrayals of sex for which reggaeton is known, even while deploying its bedrock rhythm.

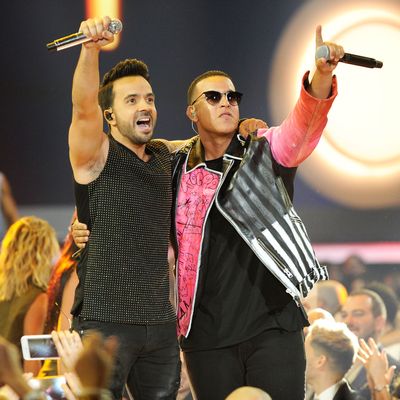

One might hear “Despacito” as a successful bourgeoification of the genre, making reggaeton even easier for middle-class masses to consume, not unlike what Juan Luis Guerra did for bachata in the 1990s. This smoothing of rough edges, however, is carefully mitigated by the contributions of Daddy Yankee, at once a seasoned pro like Fonsi and Ender and a hard-core reggaetonero — a pioneer who has been rapping in Spanish over reggae beats since well before San Juan’s homegrown genre had a name of its own. Most familiar to audiences from his 2005 smash, “Gasolina” (one of the few reggaeton songs to make an incursion into the U.S. pop charts), Yankee brings his street-level credibility and pop savvy to the proceedings, including a blistering verse and refrain that carry the second half of the song.

But let’s talk about the chords. Reggaeton is not generally known for its harmonic content, and indeed, “Gasolina” is animated by a simple alternation between semi-tones — not exactly the stuff of Tin Pan Alley. “Despacito,” on the other hand, makes use of four of the most common chords in popular music over the last century. More precisely, the song employs an ordering and arrangement of these chords which has been utterly ascendent since the turn of the millennium. The tried-and-true harmonic progression of “Despacito” is absolutely key to its success.

You may have seen the popular video “4 Chords” by the Axis of Awesome in which four guys cycle amusingly through 50 pop songs in six minutes, interweaving recycled harmonic structures to great effect. At any rate, you’ve certainly heard these chords before, over and over again. Using the Roman numerals of music theory, we could label them I, IV, and V, the bread and butter of the blues, along with the minor chord, vi. In the key of C, that would be C major, F major, G major, and A minor. The four chords can be arranged in several ways, and the Axis of Awesome make use of this by shuffling through songs which contain different orderings, using their common chords to pivot.

Certain orders of these chords, such as I-vi-IV-V, have been labeled the “doo-wop” progression or the “ice-cream changes” because of their use in dozens of mid-century pop songs (think “Blue Moon” or “Heart and Soul”). Another arrangement, I-V-vi-IV, has been dubbed the “pop-punk” progression and has outpaced the “doo-wop” version over the last few decades. Closely related is the progression used by “Despacito”: vi-IV-I-V, which begins on the minor chord and then cycles through the major ones, creating a sense of suspense and unresolvedness. This particular order has been enjoying a remarkable resurgence over the last 20 years, as chronicled by journalist Marc Hirsh who first drew attention to the growing popularity of this permutation of power pop’s favorite chords back in 2008. Hirsh maintains a list on his blog of songs that use this particular ordering, and in the last ten years, such instances have ballooned.

While dozens of hits employ this chord progression, there are two distinct branches of those that do: songs that change chords every two beats (Roxette’s “Listen to Your Heart,” Joan Osborne’s “One of Us”, Beyoncé’s “If I Were a Boy”) and songs that change every four beats or every full measure. “Despacito” shares the latter form: one bar for each chord, a pacing that builds and resolves an epic sense of tension. The song shares this arrangement with some of the biggest hits in pop (whether rock, rap, EDM) in the last 30 years: Smashing Pumpkins’ “Disarm” (1993), the Cranberries’ “Zombie” (1994), Avril Lavigne’s “Complicated” (2002), OneRepublic’s “Apologize” (2006), Akon’s “Beautiful” (2008), Lady Gaga’s “Poker Face” (2008), Eminem’s “Not Afraid” and “Love the Way You Lie” (2010), Tiësto’s “Red Lights” (2013).

These four chords would have been a canny choice for “Despacito” for this reason alone, tapping musical memory even in a foreign language, but the resonance of these chords extends beyond the world of pop music. As music theorist Scott Murphy has pointed out, the vi-IV-I-V chord progression — and this particular one-bar-per-chord instantiation — has become conspicuously common in scores for films and, even more frequently, for trailers. Murphy traces this trend to Hans Zimmer’s mainstreaming of pop progressions, especially the vi-IV-I-V as a “heroic signifier,” in such scores as Days of Thunder (1990) and most influentially, Gladiator (2000), which film scholars identify with the return of the epic film. Since then, the vi-IV-I-V has propelled such scores as Chicken Run, Pirates of the Caribbean, Chronicles of Narnia, Sunshine, Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs, The Avengers, Iron Man 3, and many more. It appears even more frequently in trailers, even when the chords are not part of the film’s score, instantly dramatizing the heroic premises of such films as X-Men Origins: Wolverine, Star Trek: Into Darkness, Unbroken, even the Venus and Serena documentary. While they have not garnered as much attention as the beat, lyrics, or vocal performances in “Despacito,” these four chords — and their remarkable contemporary resonance — are clearly one of the song’s biggest, subtlest hooks.

All of these elements — the lyrics, the chords, the performances, and the production — combined to make “Despacito” a runaway hit in the Spanish-speaking world, and on global platforms like YouTube and iTunes, well before a fateful night in April when Justin Bieber heard it at a club in Bogotá and decided he’d like to hop aboard. By that time — indeed, even by the end of January — the song had already shot to No. 1 in a dozen countries and was outcompeting Bruno Mars on iTunes. It remains telling that while the Bieber “remix” has been garnering most of the airplay in the U.S. and has given a serious boost to the song’s popularity, it is the original video featuring Fonsi and Daddy Yankee that has racked up 3 billion views. (Bieber’s version, posted to his VEVO, has only half a billion.)

Tropical Pop as Platform

While “Despacito” has clearly already become a platform in its own regard — for Bieber and for countless versions proliferating on YouTube (including a delightful “Indian Classical” take) — the current vogue for “tropical” sounds in pop music provided a crucial platform for Fonsi and his all-stars. Ironically, a spate of recent pop hits using the same Afro-Caribbean rhythm that underpins “Despacito” helped to make Fonsi’s song familiar and legible to Anglophone audiences. The tropical turn in pop, so far best exploited by acts from the U.S. and the U.K., has thus potentially opened the door to artists hailing from the actual places where reggae, reggaeton, and other modern Afro-Diasporic dance music have been developed.

With the exception of Rihanna, who grew up in Barbados, and perhaps Drake, who hails from the Caribbean city of Toronto, most of the artists who have stormed the charts deploying forms developed in Jamaica and Puerto Rico have been conspicuous outsiders to those music cultures. Justin Bieber’s 2015 hit “Sorry” (now over 2.7 billion views) seduces with an electronic beat that Skrillex would never have imagined without reggaeton and its EDM cousin, moombahton. Ed Sheeran’s “Shape of You,” released earlier this year and already up to 2 billion views, owes dancehall reggae money. Ariana Grande’s “Side to Side” (2016, 1 billion views) sounds an awful lot like it was built atop a subtle rearrangement of Junior Reid’s “One Blood.” The list goes on and on.

Two earlier songs offer an even closer template for the remarkable success of “Despacito.” Don Omar’s “Danza Kuduro” (2010, 1 billion views) is the biggest hit by a reggaetonero besides “Gasolina” and “Despacito.” It offers an uptempo take on reggaeton rhythms via the Angolan genre kuduro, and it is, notably, propelled by a vi-IV-I-V chord progression that gives it the same romantic lift as Fonsi’s smash. But perhaps the most clear precedent for an “undercover reggaeton” song becoming a massive hit is Shakira’s “Hips Don’t Lie” (2005), a totally ubiquitous song in its day and one of the best-selling singles of the 21st century. Listeners may not hear the song as reggaeton at all, but not only was it produced during reggaeton’s previous pop heyday, producer Wyclef Jean endowed it with a powerful loop, the very same sample that underpins most reggaeton songs.

What drives “Despacito” is an irresistible beat that most Puerto Ricans would call dembow, a rhythmic pattern deeply woven across Afro-Diasporic time and space but first and most influentially modernized — made electronic — by Jamaican producers in the 1980s. Indeed, while dembow has become a broadly applied term for any song underpinned by a steady four-on-the-floor kick drum and a 3+3+2 snare drum cross-rhythm, the word itself comes from a 1991 Jamaican recording by Shabba Ranks called “Dem Bow,” which was replayed, sampled, and spliced into the lion’s share of reggaeton songs.

While this distinctive electronic approach derives from Jamaica and Puerto Rico, the basic rhythm has been around for a long, long time. It is one of the primary rhythms of the ring shout, the oldest African-American musical institution, and it is known as the basic “tresillo” cell in Cuba, a crucial component of clave rhythms. It threads its way through the music of the Americas, whether traditional or modern, sacred or secular, and it might best be understood as a foundational musical creolization for the Americas, an Africanization of European “common time” or 4/4: the “Afro duple,” if you will. It appears as such in published form as early as 1849 in Bamboula: Danse des nègres, an attempt by New Orleans composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk to depict the songs and dances of Congo Square. It animates the ragtime-era compositions of Ernest Hogan and W. C. Handy and pops up frequently in early jazz. But this rhythm has ebbed and flowed throughout the history of U.S. pop, dethroned for decades by boogie-woogie’s 12/8 shuffle.

In a video produced by the website Genius, the Colombian producers of “Despacito,” Andrés Torres and Mauricio Rengifo, break the track down to its individual “stems” to let us hear all the layers in the deeply textured sound of “Despacito.” At one point, they reduce it to a fully synthetic backing track that wouldn’t be out of place on a 2005 reggaeton mixtape; at others, they highlight elements drawn from Colombian cumbia and traditional Puerto Rican music (the timbal, the cowbell, the cuatro that opens the song and improvises, subtly, throughout — on three separate tracks), all played live by humans. Torres and Rengifo also note that they were careful — not unlike Fonsi and Ender in the lyrics — to ensure that the production wouldn’t be hobbled by the licentious reputation of reggaeton. They explain that they were “trying to do reggaeton without doing reggaeton” on the track, and they discuss how “risky” it was for an established balladeer like Fonsi to “do the urban thing.”

“We think that reggaeton is pop now,” says Rengifo. “You don’t have to treat it like this urban, dark thing.” This is at once a straightforward description of the profound way that reggaeton has reshaped Latin pop, disappearing into it. It is also a fairly bald way of summing up the “tropical” turn in pop more generally. To be so explicit about gentrifying a genre might seem bold, but this is a longstanding pattern in the history of popular music. A litany of working-class dance music associated with public acts of bodily pleasure — and accordingly racialized as threats to the social order — has been subjected to this process, edges polished soft for mass consumption by the middle class: reggae, salsa, merengue, bachata, cumbia — and, of course, rock and jazz.

In contrast, note that Daddy Yankee has insisted on holding the torch aloft for reggaeton. “This No. 1 is not Daddy Yankee’s,” he announced in July after becoming the most streamed artist on Spotify. “It’s the entire genre’s.” Switching from Spanish to English for his new fans, he added, “We’ve been on this wave for a long time. Now it feels good that the whole world gets to surf with us.”

In that light, it bears repeating that the “tropical” wave is not just a newfangled industry concoction: It is the product of decades of Caribbean immigration, of new generations with hybrid tastes, and of intensified and international media circulation. “Despacito” is one spectacular product of this grassroots globalization, a phenomenon amplified by the network effects of such shared sites as YouTube and Spotify. While “Despacito” may be guilty in its own ways of riding this wave, it’s stunning success might yet herald something else: that this wave is the harbinger of a sea change.

YouTube World

Along with the likes of iTunes and Spotify, YouTube has frequently been cited as a disruptive force in the music business. The characterization often centers on disputes around copyright and monetization, but “Despacito” may stand as a testament to another profound form of disruption: global, multilingual audiences now play a more direct role in shaping our collective sense of the popular.

Prior to 2013, U.S. pop charts were still strictly measures of U.S.-based record sales and airplay, but with the incorporation of YouTube data, the game has changed. When Billboard recalibrated in February of 2013, adding views of official videos as well as derivative works to their complex tallies, Baauer’s “Harlem Shake” shot to the top of the Hot 100 and “Gangnam Style” galloped its way back up the chart. It is hard to imagine “Despacito” cracking the Hot 100 — never mind sitting atop it for weeks — without racking up almost a billion views on YouTube before the Bieber version was even released.

While a glance at the Top 50 most-viewed videos of all time reveals a dogged dominance by Anglophone pop stars like Bieber, Katy Perry, and Adele, there are some strong showings from Spanish-language acts such as Enrique Iglesias (“Bailando” holds the number No. 8 spot with 2.3 billion views), Shakira at No. 24 (with one of her Spanish songs), J Balvin at No. 35, and Nicky Jam at No. 45. Nearly all of them are pop songs running miles in reggaeton’s shoes, or just straight up reggaeton. And, of course, there’s “Despacito” at No. 1.

YouTube views permit a new kind of participation in the making of popular music, and the rest of the world now has a vote. We have yet to grasp the implications of this shift, but one result is that we’ve spent the first half of 2017 singing along in Spanish and winding our waists to an Afro-Caribbean beat. In a moment of resurgent isolationism and xenophobia, there is something reassuring about a popular vote that elevates our unofficial second language to No. 1 for most of Trump’s tenure to date.

For his part, Luis Fonsi seems to think the implications could be profound. “It says a lot about where Latin music is nowadays and where our culture is. We’re breaking barriers down,” he told an interviewer in May, adding, “I think that’s the biggest win out of all of this.”

Could “Despacito” be both part and parcel, effect and cause, of a true shift in popular culture? Only time will tell whether this is but another flash-in-the-pan “Latin boom” or the beginning of a new world musical order. Students of Latin pop, especially reggaeton, should know better than to assume popular success is tantamount to a kind of demographic and cultural arrival. Whether or not the barriers falling include barriers to participation for less-favorably positioned artists than Fonsi and company is perhaps the most crucial question of all. (I just heard J Balvin played in the middle of the day on my local hip-hop/R&B station, so a “Despacito” effect may be underway.)

If more of us, everywhere, are able to participate in the collective making of public culture, there’s no reason that the world as we know it couldn’t change radically — and maybe not all that slowly.

Wayne Marshall is an ethnomusicologist who teaches music history at Berklee College of Music. He is the co-editor of Reggaeton (Duke University Press, 2009).