It would not cross the mind of many critics of neoliberalism to call on the testimony of the angel Raphael in Milton’s Paradise Lost. But if the case you wish to make is as ambitious as Eugene McCarraher’s, then a witness to prelapsarian times comes in extremely handy. When Raphael explains to Adam the lie of the land in the garden of Eden, he tells him: “God hath here/Varied his bounty so with new delights/As may compare with Heaven.” The paradisiacal economy obliges “no more toil than sufficed/To recommend cool Zephyr, and made ease/More easy”. Abundance reigns. But once Satan finds his way in, writes McCarraher, “this earthly beatitude ends, and the sinful regime of toil and accumulation commences”. All the way to Donald Trump.

It is almost impossible to categorise Enchantments of Mammon. This monumental labour of love took two decades to write. There have been marvellous studies of contemporary capitalism published in recent years, for example Wolfgang Streeck’s How Will Capitalism End? But this is an extraordinary work of intellectual history as well as a scholarly tour de force, a bracing polemic and a work of Christian prophecy. It perhaps should have been at least three books. But it is beautifully written and a magnificent read, whether or not one follows the author all the way to his final destination in this journey of the pilgrim soul in the capitalist wilderness.

McCarraher challenges more than 200 years of post-Enlightenment assumptions about the way we live and work. He rails against “the ensemble of falsehoods that comprise the foundation of economics”, which offer “a specious portrayal of human beings and a fictional account of their history”. Homo economicus, driven by instrumental self-interest and controlled by the power of money, is condemned as a shabby and degrading construct that betrays the truth of human experience. After capitalism has delivered what the author describes as “two centuries of Promethean technics and its irreparable ecological impact” there must be a return to an earlier, gentler, more sacramental vision of the world; one that has a greater sense of natural limits and a restored sense of wonder at creation.

It will be a long haul to get back to that spirit. To demonstrate this, McCarraher embarks on a kind of genealogy of neoliberal morals, barrelling his way through the tracts, studies, theories and literature that have constituted the “symbolic universe” of capitalism since the Renaissance.

From the English Puritans who made money for the greater glory of God, through the machine idolatry rampant in 1920s Fordism, to the cult of the ruthless entrepreneur – most recently sanctified in the election of Trump – capitalism is best understood, he concludes, as a secular faith. It operates through myths and dogma, just as any religion does.

Modernity is not, as Max Weber maintained, the culmination of a process of intellectual “disenchantment”, in which societies lost their sense of the sacred and embraced the rational. Instead, a different enchantment took hold of our minds; the material culture of production and consumption. “Its moral and liturgical codes are contained in management theory and business journalism,” writes McCarraher. “Its iconography consists of advertising, marketing, public relations and product design.”

This brave new era produced a “predatory and misshapen love of the world”. Spiritually diminished by the commodification of things and people, and the desire to consume, we have lost sight of what the Catholic poet Gerard Manley Hopkins described as the “dearest freshness deep down things”.

In wonderfully subtle prose, McCarraher presents us with a dazzling array of characters caught up in capital’s spell. Some are intriguing, some sinister and some are borderline bonkers. Early on we encounter a 15th-century Gordon Gekko figure in the Renaissance humanist Poggio Bracciolini, author of a theologically risky treatise entitled On Avarice. This work, says McCarraher, signalled a transition: the growth of commerce and banking was beginning to loosen the grip of biblical disdain for “filthy lucre”. Bracciolini is careful to note that avarice is a sin. But the Florentine then makes an argument that is precociously modern, suggesting that without it, there would be “no temples, no colonnades, no palaces…” When, in 1515, Erasmus tells his portraitist to paint him with his purse, while wearing an ostentatiously expensive gown, the acquisitive genie is clearly out of the bottle.

The 17th-century Puritans are presented as a capitalist “avant garde”, driven by notions of a divine calling to turn common land into private property and then turn a profit on it. McCarraher quotes Gerrard Winstanley, champion of the Diggers movement, on the iniquity of the enclosures, which let loose the demons of possessive individualism. Money, writes Winstanley in A Declaration from the Poor Oppressed People of England, becomes “the great god that hedges in some, and hedges out others”.

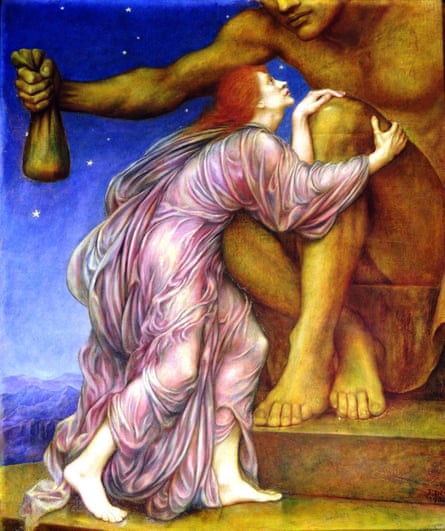

Milton mourns this sellout of the English revolution, using Paradise Lost to portray Mammon as a fallen angel, driven to blasphemous self-aggrandisement on earth. But by the 20th century such satanic cunning is the new common sense in business circles. As the new dispensation gathers momentum, McCarraher leaves the poetry of Milton to move, via the Industrial Revolution, to the outlandish business utopias dreamed up in early 20th-century America. The work of King Camp Gillette, the famed inventor of the safety razor, sets the tone. “Heaven will be on Earth,” he writes in his utopian tract World Corporation (1910). The future will be run by “Man Corporate [who] absorbs, enfolds, encompasses and makes the world his own. He will do work; he will penetrate the confines of space, and make it deliver up its secrets and powers. For Mind, the Child of the Great Over-Soul of Creation, is Infinite and Eternal.”

In February 1928, Vanity Fair caught the mood, praising Henry Ford as “a divine master-mind”, while in Nancy Mitford’s 1951 novel The Blessing, the businessman Hector Dexter embodies the evangelical zeal driving America’s new version of Eden. “I should like to see a bottle of Coca-Cola on every table in England,” Dexter tells his English lunch companions. “When I say a bottle of Coca-Cola … I mean an outward and visible sign of something inward and spiritual, I mean it as if each Coca-Cola bottle contained a djinn, and as if that djinn was our great American civilisation ready to spring out of each bottle and cover the whole global universe with its great wide wings.”

As western capitalism enters the stable prosperity of the postwar golden age, McCarraher highlights Alan Harrington’s wry account of life working for Standard Oil. One passage of Life in the Crystal Palace gives psalmic form to the consolations of life as an organisation man: “A Mighty fortress is our Palace; I will not want for anything.../I am led along the paths of righteousness for my own good. It guards me against tension and fragmentation of my self. It anoints me with benefits.”

There is much, much more, as McCarraher deals with, among others, the scary Ayn Rand, post-Catholic Andy Warhol and the writer Richard Brautigan’s tech-utopian poetic dream of All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace. All of it is selected and presented with verve. But the epilogue of this mammoth portrait of the religious longings at the heart of secular materialism carries a bleak message: 20th-century fantasies of the world as one global business have been realised. Capital’s empire now extends to all corners of the world. Globalisation has built a “paradise of capital”. But Mammon is delivering an unsustainable future dominated by wage stagnation, tech-led unemployment, deepening inequality and environmental peril. As disaster looms, distraction is being sought in “a tranquillising repertoire of digital devices and myriad forms of entertainment” along with “the analgesic pleasures of consumption”.

The solution, as Joni Mitchell might put it, is to “get back to the garden”. A new Romantic left is needed to reinhabit a sacramental imagination, which values people and things in themselves rather than as factors of production, and places collaboration over competition. McCarraher revisits the British Romantic tradition of the 19th century, recalling John Ruskin’s principle of “amazement”, which teaches that the gifts of nature should be admired and nurtured, rather than ravished and depleted. He rereads William Morris’s News from Nowhere and William Blake’s poetry, invokes the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement, and celebrates the farms pioneered by Dorothy Day’s Catholic Workers, who seek a fuller, humbler life in which they “milk cows in the morning, plough in the afternoon [and] study Aquinas in the afternoon”.

Most strikingly, perhaps, McCarraher mourns the brief life of the Occupy movement, which startled New York in 2011, observing that: “The Occupiers rebuked the callous and insouciant rapacity that had marked the previous three decades. With the free provision of food and medical care... a gift economy had supplanted the mercenary order of accumulation. Alas, it seemed that humankind cannot bear too much of heaven: Occupy and its tongues of fire were quickly extinguished or exhausted.”

The author’s dogged idealism is uplifting. But Romantic countercultures have had an unsuccessful time challenging the church of Mammon. Sometimes, as McCarraher notes, their ideas have simply been monetised and co-opted into the next wave of capitalist accumulation. And at least some readers may be less surprised than he is at how hard it is to live in heaven, given the expectations there. There seems to be little sense here of original sin, or the tragic dimension to life.

But it feels wrong to quibble with a book that is so refreshingly original and splendidly pulled off. In any case, where pessimism might take hold, the author’s Christian faith gives him a trump card. For McCarraher, it is simply the case that “the Earth is a sacramental place, mediating the presence and power of God”. That cannot change, however obscured the truth is by a destructive lust for power and accumulation. It is simply a question of seeing things as they truly are.

Some secular romantics might not be able to go along with that. But that should not make this remarkable book any less enjoyable for them to read and mull over in alarming times.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion